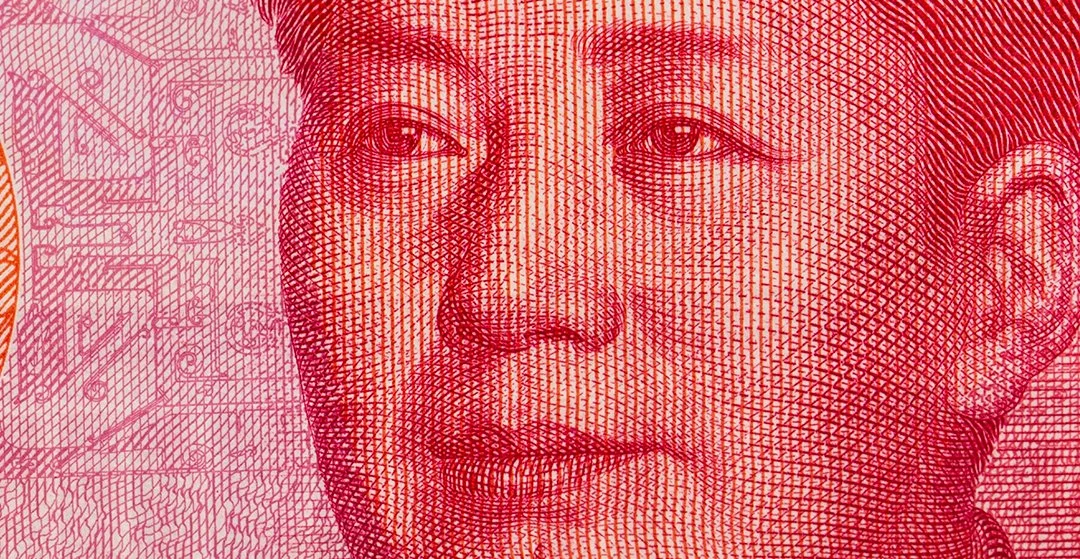

Unmasking Mao

By Matthew Califano

This review appears in the Summer 2024 issue of the Coolidge Review. Request a free copy of a future print issue.

Mao: The Unknown Story

by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (Knopf, 2005)

The rise of China has become a major concern for American foreign policy experts. But the man who sparked that rise—transforming China from a patchwork of warring fiefdoms into the world’s largest communist nation—remains poorly understood.

Mao Tse-tung has been dead for nearly fifty years, but his influence endures.

With China on the ascent, it is worth revisiting Jung Chang and Jon Halliday’s authoritative biography Mao: The Unknown Story, first published in 2005. This meticulously researched volume runs more than 800 pages, including 150 pages of endnotes. Mao is both a brilliant profile of one man’s megalomaniacal ambitions and a vivid history of a nation and culture in the throes of violent revolution.

EVANGELIZING COMMUNISM

One of the world’s most famous communist guerrillas was the son of a peasant farmer who had grown rich as a result of his almost superhuman work ethic. Mao, Chang and Halliday tell us, did not inherit his father’s dedication. The father disdained his son’s laziness and pseudo-intellectual ambitions. Mao ran away to attend school in Changsha, where he lived as an impoverished and embittered young man. There he discovered his only real ambition: achieving power and wielding it against anyone and everyone who threatened his grandiose sense of himself.

In Shanghai a few years later, Mao became a member of the Communist Party—then a small group financed by the Soviet Union to evangelize Communism in Asia. Through a combination of luck and wanton disregard for human life, he rose through the ranks to become party chairman.

Mao consolidated his power within the party while playing his enemies—the Japanese and the Chinese Nationalists—off each other during the Second World War. During the Chinese Civil War that followed, Mao asserted his power across all of China. In 1949 he forced the Nationalists to flee to Taiwan, where they established China’s modern cross-strait rival.

On the mainland, the People’s Republic of China was born. Freedom died there soon after.

The authors pay particular attention to interrogations and torture that Mao personally oversaw.

MORE THAN A MILLION DEAD

Mao remained unsatisfied. Although he had seized the commanding heights of power and lived like the Chinese emperors of old, he yearned for the adoration his hard-nosed father had denied him as a child. Chang and Halliday suggest that the Cultural Revolution sprouted from this emotional wound.

The Cultural Revolution began in 1966 and lasted until Mao’s death a decade later. This sweeping attempt to root out dissidents and assert the power of the Communist Party resulted in the deaths of more than a million people.

Mao also established his cult of personality. Under his direction, hundreds of thousands of children were enlisted as “Red Guards.” Armed with party-issued copies of Quotations from Chairman Mao, the Red Guards denounced and attacked anyone who did not display sufficient enthusiasm for Mao or his ideology. In interviews, Chang has discussed the horror of seeing the Red Guards assault her teachers and neighbors.

Despite the suffering he caused, Mao remained convinced of his own genius. During the Four Pests Campaign, Mao ordered the extermination of every sparrow in China. He believed that killing the sparrows—the bane of many a farmer’s storehouse—would help a still-agricultural China prosper. Instead, the absence of the sparrows caused the population of grain-eating insects to explode. This was one of the radical policies which led to a famine that, by conservative estimates, killed 23 million people.

In many other ways, Mao was, unfortunately, successful. Under his leadership, China became a nuclear power and broke free of the Soviet Union.

Today, Mao remains a figure of reverence in the Chinese Communist Party. In a speech delivered in the last days of 2023, China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, hailed Mao as “a great patriot and national hero in modern Chinese history,” and “a great man who led the Chinese people to change their destiny and the nation as a whole.”

China has become more aggressive in advancing what Xi calls its global “influence, appeal, and power.” As Mao: The Unknown Story shows, these ambitions trace their beginnings to Mao’s lifelong obsession with making China an indomitable power. Mao made China a regional power but failed to make it as globally influential as he had hoped.

His successors believe they can realize this final goal. Their massive international infrastructure project, the Belt and Road Initiative, has become a key piece of their effort to extend their geopolitical influence.

TRUTH WILL OUT

Mao offers a riveting account of one man’s rise from provincial obscurity to authoritarian infamy—and of a nation’s descent into bondage. Mao’s life has always been a subject of fascination, but until Chang and Halliday’s publication, his Communist Party acolytes carefully controlled information about their leader, reverently known as the “Great Helmsman.” Chang and Halliday’s thoroughly researched account pierces the veil of secrecy surrounding Mao’s life.

The authors reveal that Mao’s sadism and capricious violence exceeded the fears of even his worst critics. Chang and Halliday pay particular attention to interrogations and torture that Mao personally oversaw. Mao, they reveal, proved indifferent toward even his own children. He abandoned several and showed no concern for his son’s death in the Korean War. Chang and Halliday rely on firsthand accounts, mostly from witnesses and survivors of the Cultural Revolution, as well as exiles, to inform their work. Critics were quick to argue that some of their interviewees were of advanced age and unlikely to recollect the events of their youth with great accuracy.

But why did the authors need to turn to such eyewitness accounts? Because the Chinese Communist Party had destroyed or censored so many other sources of information on Mao’s evils.

The obstacles the authors encountered in their research reflect the Communist Party’s ongoing efforts to obscure its history of brutality and its sinister ambitions. Chang and Halliday have, however, succeeded in dragging the truth about Mao into the light.

Matthew Califano, a 2023 Coolidge Scholar, is a student at Yale. Mao: The Unknown Story was the inaugural selection of the Coolidge Honors Book Club.